Obviously, the most prominent sports journalist of his era would name the man who made Cosell famous: Ali.

Wrong.

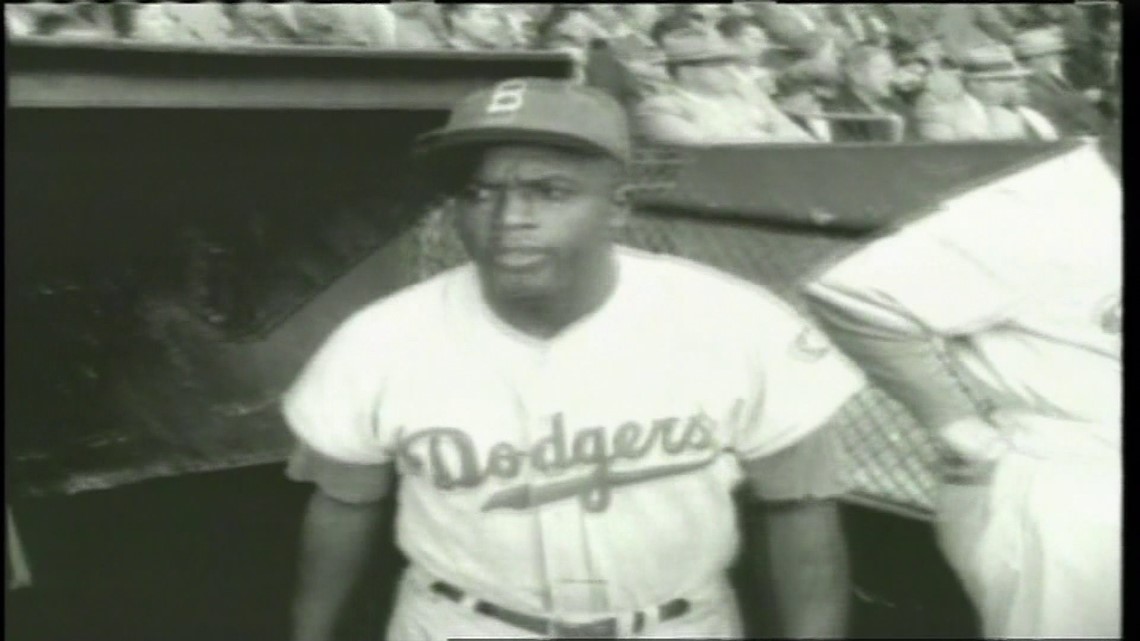

“That’s an easy one,” Cosell said, spacing out the name with inflection, “Jack … Roosevelt … Robinson.”

Cosell was just telling it like it is. Muhammad Ali’s global impact is irrefutable as a champion boxer and outspoken critic of America for its involvement in Vietnam and civil rights oppression at home. But in breaking the long-standing racist color line of America’s pastime in 1947, Jackie Robinson’s contribution to American society was much more profound.

Yes, No. 42 was “The Greatest.”

Everyone, particularly people of color, owes a debt to this courageous man who made Stamford his home. As the first African American to play Major League Baseball, Robinson took the insults, slurs, threats and abuse and made it just a little bit easier for the next person of color to become “first” and second in their workplace or school.

I recently saw the movie ” 42,” which has been a box office success. Frankly, the movie did not reveal much of what this Jackie Robinson fan didn’t already know about Robinson’s trials and triumphs. The film, however, did provide important perspective about the historical relevance of Robinson’s life and accomplishments.

The other day a Facebook poster, an African American male, offered a contrarian perspective on all the attention paid to “42” and questioned Robinson’s overall impact on American society and race relations. The poster said Robinson did not change the contentious dynamics of race relations in America or the continuation of white privilege. He challenged whether black progress could be measured by Robinson’s career.

Jackie Robinson’s Legacy As ‘The Greatest’

Perhaps he should pose that question to Willie Mays and Hank Aaron and Derek Jeter and the scores of millionaire African American professional athletes who came after Robinson. Barack Obama may offer a point of view on Robinson’s contribution to his ascension as well, as would some of the black titans in business, law, health care and politics. Robinson’s legacy is not measured so much in tangible progress, but in the intangible inspiration and motivation he engendered.

Sharon Robinson, Jackie’s daughter, said her dad was humbled when the Little Rock Nine, the black students famous for integrating Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas in 1957 — the year Robinson retired and a decade after he integrated baseball — told Robinson that he was their hero.

Robinson’s journey, the Little Rock Nine, Rosa Parks and a Supreme Court ruling decrying “separate but equal” public schools all provided inspiration for the 1963 March on Washington.

Robinson’s agreement to not fight back against the taunts and slurs of his opponents, teammates and fans was the ultimate example of his resolve and character. Turning the other cheek was not his true nature. Robinson was educated at UCLA and was an Army second lieutenant once court-martialed — and later exonerated — for refusing orders to sit in the back of a bus.

Nearly 70 years after he broke baseball’s color line, a new generation is showing its appreciation to Jack Roosevelt Robinson. It’s reflected at the movie box office and the exploding sales of Robinson-related memorabilia. In recent years, the No. 42 Brooklyn jerseys with “Robinson” on the back topped merchandise sales of current baseball stars.

There has always been an underplayed business element to Robinson’s integration of baseball. Dodger executive Branch Rickey and manager Leo Durocher were supporters. But their primary motivation was not integration. They wanted to win. Robinson added value to the team on the field and at the gate. He was America’s first taste of affirmative action, before that term became demonized. He was a qualified black applicant denied the opportunity to advance in his chosen profession in an institutionally racist industry. Amends had to be made. His Hall of Fame career subsequently spoke for itself.

The latest wave of Robinson appreciation hopefully will inspire more young African American kids to play baseball. The percentage of African American ballplayers in the big leagues has decreased to 8 percent — a 50 percent drop in the last 27 years and the lowest level since the sport’s integration.

Robinson surely would be perplexed by this measure of progress.