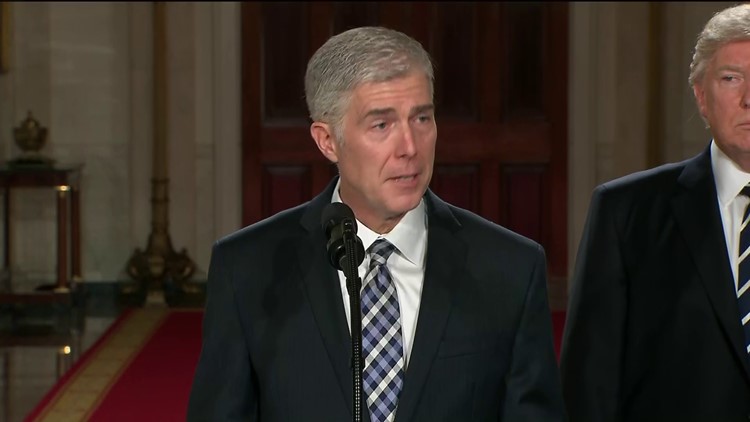

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump nominated Colorado Judge Neil Gorsuch for the vacant position on the Supreme Court.

The 49-year-old Gorsuch sits on the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Trump’s nominee will replace conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, who died suddenly at a remote Texas hunting resort last February.

The nomination of Gorsuch, a 49-year-old federal appellate judge from Colorado, gives Trump and Republicans the opportunity to confirm someone who could cement the conservative direction of the court for decades.

His selection also sets up an intense fight with Senate Democrats, still angry over the Republicans’ decision to essentially ignore former President Barack Obama’s nomination of Judge Merrick Garland for the empty Supreme Court seat last year.

Introducing Gorsuch, Trump said he had committed as a candidate to “find the very best judge in the country for the Supreme Court.”

“Millions of voters said this was the single most important issue for them when they voted for me for president,” Trump said. “I am a man of my word.”

“Today I am keeping another promise to the American people by nominating Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court.”

The court has been operating with eight justices since the sudden death last February of Justice Antonin Scalia. If confirmed, Gorsuch would continue the ideological balance that existed before Scalia’s death, with four conservatives, four liberals and Justice Anthony Kennedy as a swing vote between the blocs.

Trump selected Gorsuch — who sits on the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals — from a list of 20 potential justices compiled during the presidential campaign in a direct appeal to conservative and evangelical voters skeptical about his commitment to their values.

Gorsuch’s opinions on religious liberty, where he sided with the challengers to the so-called Obamacare contraceptive mandate, and on the separation of powers, where he said too much deference was given by the courts to administrative agencies, are key to his appeal to Republicans. As is his age. At 49, he could carry on Trump’s legacy long after the President leaves office.

Gorsuch’s legal philosophy

Unlike others on Trump’s list, Gorsuch has an Ivy League pedigree, having attended Columbia and Harvard, and also studied at Oxford, where he earned a doctorate in legal philosophy.

Gorsuch is a fourth-generation Coloradan and a former clerk to both Justices Byron White and Anthony Kennedy.

“It is an extraordinary resume. As good as it gets,” Trump said.

“The qualifications of Judge Gorsuch are beyond dispute,” Trump said. “I only hope that Democrats and Republicans can come together for one, for the good of the country.”

On the bench he joined an opinion siding with closely held corporations who believed that the so-called contraceptive mandate of Obamacare violated their religious beliefs. The ruling was later upheld by the Supreme Court. Gorsuch wrote separately holding that the mandate infringed upon the owners’ religious beliefs “requiring them to lend what their religion teaches to be an impermissible degree of assistance to the commission of what their religion teaches to be a moral wrong.”

He also wrote a majority opinion in a separation of powers case holding that too much deference was given to administrative agencies. This issue is a favorite of conservatives and Gorsuch’s beliefs align with those of Scalia and Justice Clarence Thomas.

Gorsuch, in a speech last year at Case Western Reserve University School of law, aligned himself with Scalia’s judicial philosophy.

“The great project of Justice Scalia’s career was to remind us of the differences between judges and legislators. To remind us that legislators may appeal to their own moral convictions and to claims about social utility to reshape the law as they think it should be in the future, ” he said. “But that judges should do none of these things in a democratic society.”

At the White House Gorsuch he would faithfully commit to upholding the laws of the nation, saying he would act as a “servant of the Constitution and laws of this country.”

Like Trump, he cited Scalia as a model.

“Justice Scalia was a lion of the law,” he said.

Democratic opposition and the ghost of Garland

Senate Democratic leaders instantly painted Gorsuch as an extremist and said he must get the 60 votes needed to break a filibuster.

“Judge Gorsuch has repeatedly sided with corporations over working people, demonstrated a hostility toward women’s rights, and most troubling, hewed to an ideological approach to jurisprudence that makes me skeptical that he can be a strong, independent justice on the court,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer said in a statement.

Sen. Patrick Leahy, the top Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee, said Trump “outsourced this process to far-right interest groups.”

“President Trump said he would appoint justices who would overturn 40 years of jurisprudence established in Roe v. Wade,” Leahy said. “Judge Gorsuch has shown a willingness to limit women’s access to health care that suggests the President is making good on that promise.”

For Democrats, the nomination is made worse by what happened with Garland.

When Obama nominated Garland to take Scalia’s seat last year, liberals hoped that they would get a liberal majority that would swing the court left on key issues such as abortion, campaign finance and voting rights.

But Senate Republicans refused to hold hearings, citing the impending election which was still eight months away.

Democrats have said they would fight the new nominee “tooth and nail” putting not only his or her credentials to the test, but holding Republicans responsible for what liberals say is a “stolen seat.”

After Trump’s unexpected win, conservatives rejoiced, expecting the new president to nominate someone to the bench in the mold of Scalia. They also hope that with three justices on the Supreme Court in their late 70s and early 80s, Trump might have at least one more vacancy to fill.

If, for example, Justice Anthony Kennedy were to step down, the conservatives might be able to chip away at Roe v. Wade, the landmark opinion that legalized abortion.

Mother was EPA administrator

Gorsuch’s confirmation would mean a return to Washington.

He spent part of his youth in Washington when his mother, Anne Gorsuch Burford, served in the Reagan administration as administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency.

She resigned in 1983 under controversy after refusing to turn over toxic waste records to Congress.

He served as a partner at a prestigious Washington Law firm, Kellogg, Huber as well as Principal Deputy Associate Attorney General.

Gorsuch and his wife Louise have two daughters. They live in Boulder, Colorado.

Here’s why the Supreme Court matters:

Who checks the actions of the president?

If the controversies of Trump’s nascent presidency are any indication, the nation’s federal courts will be busy attempting to resolve future legal disputes.

“That will put the Supreme Court, and potentially this new jurist, at the fulcrum of Trump’s efforts to change life in America,” Joan Biskupic, CNN legal analyst and Supreme Court biographer, wrote Tuesday.

Case in point: Trump’s order last Friday temporarily barring refugees and citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the country resulted in massive protests and a flurry of litigation.

The part of the executive order blocking entry to people from seven Muslim-majority countries — even if their visas were valid — drew the most criticism. Lower court judges temporarily suspended parts of the order.

The constitutionality of Trump’s sweeping actions will likely be decided by the Supreme Court.

Does the ideological makeup of the court matter?

The nine-member court is deeply divided along ideological lines. Every vote matters.

The dissent of a lone justice can tip the balance on major issues involving civil rights and criminal law.

Scalia’s successor will take the place of a rigid conservative on social issues such as abortion rights, affirmative action and gay marriage. Under Scalia, the court was one of the most conservative in modern times.

“Rarely has there been a moment in American history of such widespread national discord, internal court divisions, and the opportunity for a new tie-breaking justice,” Biskupic wrote.

Trump has expressed his desire for a justice who would reverse Roe v. Wade, which made abortion legal nationwide. He has said he wants states to have the power to determine when a woman has the right to end a pregnancy.

What’s the makeup of the current court?

Four Republican appointees on the bench have generally taken a conservative stance (Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito) and four Democratic appointees regularly have been more liberal (Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan).

But Kennedy’s centrist tendencies prevented conservatives from significantly rolling back abortion rights, or race-based policies intended to enhance student diversity at universities — as allowed in 1978 by Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. Kennedy was also the crucial fifth vote to declare a constitutional right to same-sex marriage in 2015.

He remains on the bench, but he is 80 years old and has indicated to some close friends and associates an interest in retiring. If he were to step down, successive nominations by Trump could transform the court and the law in America.

Ginsburg, who will turn 84 in March, is the court’s eldest justice. Breyer will turn 79 in August.

What is the primary purpose of the court?

The justices serve as the final word for a nation built on the rule of law.

They interpret the Constitution, which involves every aspect of our lives — how we conduct ourselves in society and boundaries for individuals and the government.

As the late justice William Brennan once wrote, “The law is not an end in itself, nor does it provide ends. It is preeminently a means to serve what we think is right.”

When it came to deciding who won the 2000 presidential election, for instance, the conclusions of the Supreme Court ultimately resolved the issue, even though the controversy lingers.

Why was the Supreme Court created?

The first meeting of the Supreme Court was in 1790.

The court is led by the Chief Justice of the United States (that’s the official title). All justices — and all federal judges — are first nominated by the president and must be confirmed by the Senate. They serve for as long as they choose.

The court has occupied its current building in Washington only since 1935. Previously, it borrowed space in Senate chambers in the Capitol Building.

The Constitution’s framers envisioned the judiciary as the “weakest,” “least dangerous” branch of government.

Over the years, the court has often been accused of being too timid in asserting its power. But when the justices flex their judicial muscle, the results can be far-reaching.

Consider cases such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954 — integrated public schools), Roe v. Wade (1973 — legalized abortion) and even Bush v. Gore (2000 — resolved the disputed presidential election).

How does the court work?

Traditionally, each Supreme Court term begins the first Monday in October, and final opinions are issued usually by late June.

The justices divide their time between “sittings,” where they hear cases and issue decisions, and “recesses,” where they meet in private to write their decisions and consider other business before the court.

Court arguments are open to the public in the main courtroom, and visitors have the option of watching all the arguments or only a small portion.

Traditions are observed. The justices wear black robes. Quill pins still adorn the desks, as they have for more than two centuries.

The justices are seated by seniority, with the chief justice in the middle. The two junior justices (currently Sotomayor and Kagan) occupy the opposite ends of the bench.

Before public arguments and private conferences, where decisions are discussed, the nine members all shake hands as a show of harmony of purpose.

Arguments usually begin at 10 a.m. and since most cases involve appellate review of decisions by other courts, there are no juries or witnesses, just lawyers from both sides addressing the bench. The cases usually last about an hour. Lawyers from both sides very often have their prepared oral briefs interrupted by pointed questions from a justice.

How many cases are accepted?

Each week, the court receives more than 150 petitions for review — decisions by lower courts appealed to the high court. Relatively few are granted full review. About 8,000 to 10,000 such petitions go on the court’s docket each term.

Only 75 to 85 cases — about 1% — are accepted.

Court opinions are final. The only exception is the court itself, which can over time overturn its own precedent, as it did with racial segregation. But most justices rely on the principle of “stare decisis,” Latin for “to stand by a decision,” where a current court should be bound by previous rulings.