As Jamal Knox’s conviction for rapping that he would kill two Pittsburgh police officers made its way through the appellate courts, the US Supreme Court ruled that another rapper was protected in saying he wanted to kill a federal agent.

Yet in ruling in Anthony Elonis’ favor, legal analysts worried, the high court had muddied what constitutes a true threat, the issue at hand in Knox’s case. Justice Samuel Alito expressed a similar concern — particularly in regard to social media postings — in his partial dissent to the 2015 ruling.

Where Alito held that song lyrics performed live or in a studio were unlikely to be regarded as a real threat, “statements on social media that are pointedly directed at their victims, by contrast, are much more likely to be taken seriously,” he wrote.

Knox’s legal team nodded to the confusion. In their petition to the US Supreme Court, his lawyers said that where most courts have ruled the standard is objective and requires only that a “reasonable person” would regard the speech as a sincere threat, “other courts have held that the standard is subjective and assess only whether the speaker intended to communicate such a threat.”

Rappers are rallying around Knox, but it’s unclear if Alito and company will hear his case, despite a who’s who of the hip-hop community urging the high court to do so. To them, rap music is being singled out, again, where other genres and forms of expression have been given a pass.

The Supreme Court has docketed the case, but justices have not determined whether they will hear it.

The Knox case

Knox, 25, who goes by the rap moniker Mayhem Mal, and his buddy, Rashee Beasley, aka Soulja Beaz, were arrested in 2012 after police found several bags of heroin, a gun and $1,489 in their vehicle.

As the pair awaited trial, they produced a rap song, “F*** the Police,” and posted a video to social media. Where Elonis had invoked violence in a more abstract manner — at times indicating he was testing the bounds of free speech — Knox and Beasley were specific in their targets and aims.

They referred to the arresting Pittsburgh officers by name, boasted knowledge of the officers’ schedules and laid out the violence they were willing to exact.

“I’ma jam this rusty knife all in his guts and chop his feet/You taking money away from Beaz and all my s*** away from me/Well your shift over at 3 and I’m gonna f*** up where you sleep,” Knox rhymed at one point.

Beasley went on to say he was “strapped nasty” like Richard Poplawski, a reference to the heavily armed man who killed three Pittsburgh police officers in 2009.

The song closes with Knox rapping, “Let’s kill these cops cuz they don’t do us no good/Pullin’ your Glock out cause I live in the hood.”

One of the officers testified that he was shocked by the lyrics, and he retired from the police force and relocated because of the song, while the other officer found the video “very upsetting,” leaving him concerned for his and his family’s safety. He required time off and a security detail, he testified.

Knox was convicted on two counts of terroristic threats and two counts of witness intimidation, which has been upheld by appeals courts, including the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which cited the specificity of the threats, the use of the officers’ names and the Poplawski reference.

The song, the trial court ruled, constituted a “true threat to the victims” and warranted no First Amendment protection.

Elonis’ case

Elonis, too, employed a sobriquet — Tone Dougie — and social media in posting an array of threats in a skit and in rap lyrics he posted online. Among his purported targets were employees of an amusement park from which he’d been fired, his estranged wife and elementary schools, court documents indicate. Per the latter, he wrote, “Hell hath no fury like a crazy man in a kindergarten class.”

After FBI agents visited his home, he took to Facebook to post, “Little Agent lady stood so close/Took all the strength I had not to turn the b**** ghost/Pull my knife, flick my wrist, and slit her throat/Leave her bleedin’ from her jugular in the arms of her partner.” He also claimed that if the agents patted him down, he would “touch the detonator in my pocket and we’re all goin’ (BOOM!)”

Amid posting the lyrics, Elonis alluded to a First Amendment battle, saying, “Art is about pushing limits. I’m willing to go to jail for my Constitutional rights. Are you?” In court, he contended his songwriting was cathartic, a form of therapy, and compared his lyrics to those of Eminem, who has repeatedly threatened to kill his wife and others in his music.

“The First Amendment’s basic command is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds it offensive or disagreeable,” defense attorney John Elwood wrote in a brief.

Elonis’ case — considered the US Supreme Court’s first dealings in true threats on social media — drew the support of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Despite Elonis’ claim he was a poet and entertainer and that his lyrics were a form of self-expression, he was convicted on four counts of violating a federal threat statute and sentenced to 44 months in prison, a ruling upheld on appeal until it reached the US Supreme Court.

The justices ruled 8-1 that the lower court had erred in convicting Elonis based on the assertion that a reasonable person would consider his posts threatening. Such a legal standard was too low to convict him, the court ruled.

“Our holding makes clear that negligence is not sufficient to support a conviction,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote.

The confusion laid bare

In ruling in Elonis’ favor, the high court left open what the standard should be. It was a narrow ruling and the court did not address the larger constitutional issue, which analysts at the time predicted would result in disparate rulings among lower courts.

Analyst Lyle Denniston wrote for SCOTUSblog at the time that the ruling “was based solely on the premise that he was convicted without proof that he knew what he was writing and that the ordinary meaning of his words would be a threat.”

The 1939 federal law dealing with true threats is clear in its requirement that a communication containing a threat be transmitted and that the accused is aware.

Denniston wrote, however, the ruling failed to set a standard for future rulings, as mentioned in Justice Clarence Thomas’ dissent and Alito’s partial dissent.

Alito predicted the ruling would “cause confusion and serious problems” because the majority provided only a partial answer as to what mental state was required for conviction under the law, Denniston wrote. Thomas lamented the ruling left lower courts “to guess at the appropriate mental state” required for conviction. It discarded the approach of the previous federal appeals court “and leaves nothing in its place,” Thomas wrote in his dissent.

While those might seem like heady issues, the rap community sees it in simpler terms. This is about expression, they say, and if Knox’s conviction is upheld, it will show that a different standard is being applied to rap music than to other forms of entertainment.

Rap attack?

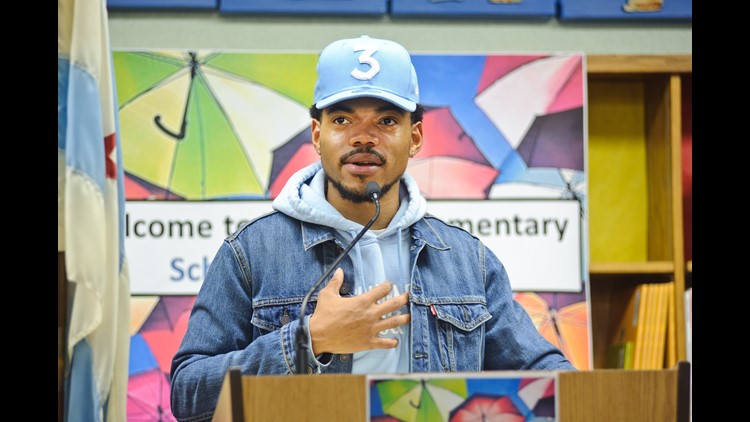

In their legal brief filed last week, scholars joined forces with rhymesmiths including Chance the Rapper, Killer Mike, 21 Savage, Meek Mill, Fat Joe and Luther Campbell, whose 2 Live Crew was integral in shaping the nation’s obscenity laws in the 1990s.

They called Knox’s song a political statement “that no reasonable person familiar with rap music would have interpreted as a true threat of violence.”

The name of the song itself, they said, pays homage to N.W.A.’s “F*** The Police,” which they dubbed “one of the most important protest songs ever written.”

Knox’s song, thus, provides the perfect vehicle for establishing the standards for whether speech is threatening and not worthy of First Amendment protection because it “not only is political in character, but is a complex form of expression characterized by multilayered messages, which leads to the possibility of misinterpretation,” they wrote.

“Furthermore, rappers famously rely on exaggeration and hyperbole as they craft the larger-than-life characters that have entertained fans (and offended critics) for decades.”

But while imploring the Supreme Court to take up the case and set a discernible standard, the rappers’ and scholars’ minds are already made up.

“A person unfamiliar with what today is the nation’s most dominant musical genre or one who hears music through the auditory lens of older genres such as jazz, country, or symphony, may mistakenly interpret a rap song as a true threat of violence and may falsely conclude a rapper intended to convey a true threat of violence when he did not,” the brief said.