CONNECTICUT, USA — Data from the Connecticut State Department of Education shows a significant rise in chronic absenteeism during the pandemic. The state defines chronic absenteeism as missing at least 10% of school.

For 8-year-old Jovanni Roman and his mom Dennice Sanchez, the problems started at the start of the pandemic with the shift to fully remote learning.

“It was so hard. He does have a learning disability so it was harder for me. He can’t stay still for the life of him,” said Sanchez.

It was a no-brainer for Sanchez to send Roman back to Martin Elementary School in Manchester in person, full-time last year when that became an option, instead of going with a fully remote or hybrid model. However, that proved easier said than done.

RELATED: Diversifying the teacher workforce in Connecticut

“He didn’t want to go to school. He wasn’t motivated. He would give me a hard time in the morning. His stomach would hurt. He has a headache," Sanchez explained. "He does have sleep problems, so he wouldn’t sleep all night. He was really tired. I was getting calls from the schools, like, ‘Hey, Jo is really tired,’ so I would sometimes take it under consideration, just let him stay home and rest,”

However, those absences started adding up throughout the year. Sanchez estimates her son missed about 27 days, maybe more.

Missing that much school made Roman chronically absent, which is defined by the state as having an attendance rate at or below 90%. In a standard 180-day school year, that’s missing at least 18 days.

“Knowing that he can’t read,” said Sanchez through tears. “Knowing that I’m a part of his struggle because I didn’t let him go to school and knowing that he’s far behind. He’s having trouble with his reading, his writing and his math.”

Seeing that learning loss pains the teachers as well.

“You get the feeling oftentimes we the teachers care more than the student does. We care more about their individual progress – their success rate – than they do and that keeps a lot of us up at night,” said Thomas Ross, a teacher at Danbury High School.

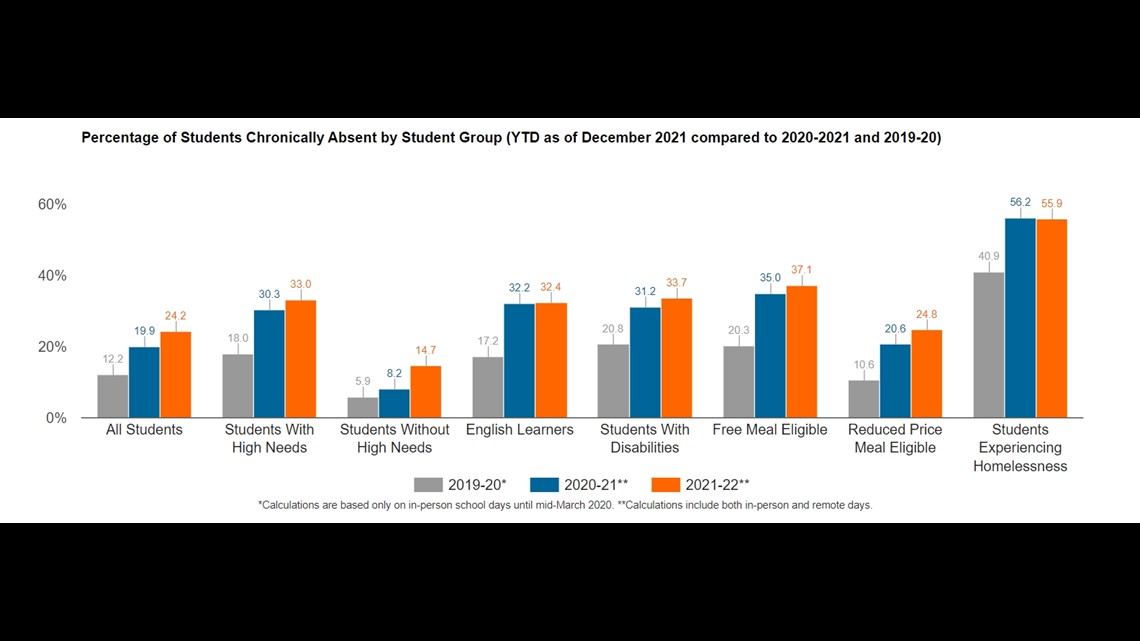

According to state data collected from school districts, just over 12% of all students were chronically absent during the pre-pandemic period of the 2019-2020 school year. During the last school year, that number jumped to nearly 20 percent. So far this school year, it’s just over 24%.

The data also shows that students with high needs who are free meal eligible, English learners or have disabilities show higher rates of chronic absenteeism than their peers.

“We encountered many, many more students in our numbers and they weren't the students that had necessarily been there before,” said Fran Rabinowitz, Executive Director of the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents.

Rabinowitz said chronic absenteeism was already a problem in some communities before the pandemic and COVID only made things worse, pointing to remote learning as a major factor.

To that end, the state made deals to provide communities with laptops and hotspots, but it was still a struggle for students.

"Let's face it: the engagement on remote learning is not the same engagement as being in front of your teacher and learning and being with your classmates and networking and collaborating and talking,” said Rabinowitz.

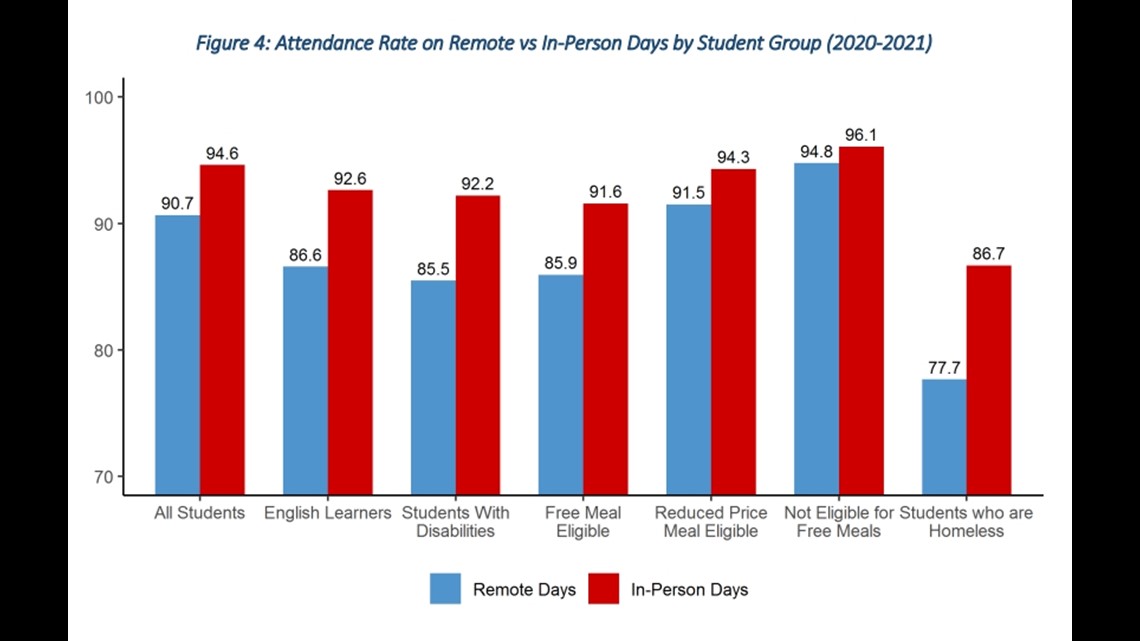

According to state data from the 2020-2021 school year, the attendance rate for all students on remote days was lower than on in-person days. The data also shows the pattern is most drastic among students with the highest needs.

“How do you intervene with these children, because we know it doesn't help anything to hold the children back a grade so to speak. We have all the studies on what happens when you hold a child back,” said Rabinowitz.

Enter the Learner Engagement and Attendance Program (LEAP), which was started by the state last year to help K-12 students struggling with absenteeism and disengagement. The program targeted 15 hard-hit school districts across the state, including:

- Bridgeport

- The Capitol Region Education Council (CREC)

- Danbury

- East Hartford

- Hartford

- Manchester

- Meriden

- New Britain

- New Haven

- New London

- Norwich Stamford

- Torrington

- Waterbury

- Windham

Through the program, support personnel go directly to homes, engage with families and students, help return them to a more regular form of school attendance and assist with placement in upcoming summer camps and learning programs.

The state said home visits also enable officials to help other critical student needs, including behavioral and mental health issues, housing, childcare, lack of technology and other educational needs.

$10.7 million of Connecticut’s federal COVID-19 recovery fund were used for the initiative.

"The governor set aside this funding to help districts. They surveyed superintendents to see what they needed beyond the computers and the hotspots and it was really manpower to help develop these relationships that teachers are really busy, but people who can go out and engage those families who need more support to come to school,” said Kari Sullivan, an education consultant with the Connecticut State Department of Education.

At Manchester Public Schools, Latasha Easterling-Turnquest leads the effort as the district’s Chief of Family Partnership and Student Engagement. She oversees student engagement specialists in elementary schools. Those positions were in-part born out of the pandemic.

"They are looking at the chronic absenteeism lists, 8-15% and they are making phone calls, they're doing Zoom meets, Google meets with families, if the family allows, which has been really tough, going into the home to do a home visit,” said Easterling-Turnquest.

All that to really understand what’s keeping students out of school.

"A second-grader or a kindergartener doesn't say I'm going to miss 40 days of school. There is definitely something going on with the family, and notice how I didn't say there is something wrong with the family,” said Easterling-Turnquest.

So, what is going on? It’s everything from mental health struggles, the fear of catching COVID, employment or transportation issues, students not having clean clothes and the list goes on.

"When you're dealing with attendance, a lot of families feel intimidated, like you're a truancy officer or you're here to get them, but we're just here to help,” said Treyvon Brown, a student engagement specialist at Manchester Public Schools.

That help can come in the form of providing alarm clocks, finding transportation or helping get students enrolled in after-school programs— whatever it takes to get students back in the classroom.

"Once you get that child in school and the family sees the child happy and they're smiling and they're doing better, it will light up your day,” said Brown.

The hope is always a happy ending, but the Department of Education is keeping a close eye on the data to better understand how these pandemic-related learning disruptions are affecting this generation’s future.

"A couple of the metrics we'll be watching more closely are the extent at which students are on track in ninth grade to high school graduation, and then we'll be watching graduation itself. How is high school graduation doing through this pandemic and those numbers are just beginning to come in,” said Ajit Gopalakrishnan, Chief Performance Officer at the Connecticut State Department of Education.

Angelo Bavaro is an anchor and reporter at FOX61 News. He can be reached at abavaro@fox61.com. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Have a story idea or something on your mind you want to share? We want to hear from you! Email us at newstips@fox61.com

HERE ARE MORE WAYS TO GET FOX61 NEWS

Download the FOX61 News APP

iTunes: Click here to download

Google Play: Click here to download

Stream Live on ROKU: Add the channel from the ROKU store or by searching FOX61.

Steam Live on FIRE TV: Search ‘FOX61’ and click ‘Get’ to download.